Art, science, taste and "clean code"

Science establishes concepts that describe nature, and is often able to signal binary answers to questions. “Can acceleration be non-0 when velocity is 0?” “What is the circumference of a circle?” “How many chromosomes does a fruit fly genome contain?”

Art, unlike science, speaks to our emotion. Great art is great exactly because - in addition to execution - it stimulates us to imagine something which makes us feel in a certain way. It is about communicating emotion.

There is a ton of talk about how “bikeshedding details” is “sophistry”, “you should not care that much”, “style reviews create opportunities for abuse” and the like. But we are, as a community, slowly moving towards optimising for two things, and two things alone:

- Making all changes we do measurable improvements. Either using objective or fake metrics which will somehow demonstrate that “we were right” or “we were wrong”

- Making nobody feel bad, ever

When we optimize in that direction, we tend to dismiss (or even discourage) “taste”, because of course it is personal, it is subjective, and it can be imposed by someone in position of authority. What we do skimp on in the process, is that “bikeshedding” design decisions - and code! - bringing back taste thus - can produce a solution which is not only “nicer”, or “pleases the loudest senior person on the team the most”. There are things we can debate in that domain, and they are all of differing orders:

- Not code formatting (just install an automatic formatter for this and move on)

- Size of modules / functions

- Granularity of modules / functions

- Verbosity / DRYness of tests

- Quality of encapsulation

While the things above are not quanitifiable, the paradox is that their outcomes can be, or at the very list they can be qualifiable. They are important and if you give them some TLC you are going to get reductions in your cost of ownership down the line.

The good questions for bikeshedding

Here are those, and I was incredibly lucky to see more than a few times when prioritizing them in bikeshedding discussions led to meaningful, useful outcomes. I like to formulate them as questions - because barking orders at each other is exactly what creates the toxic environments we overcorrected from. Let’s walk through those questions:

- How long will it take a person who never worked on your module before to read your test when there is a problem? What will be the hurdles they are going to likely encounter? What will be the cost of unpacking the abstractions you have used?

- What could we change so that the addition of your module, in total, allows us to have less software?

- Is there something in your change that is going to be difficult to understand for a person 1 level below you in seniority? 2 levels? 3 levels?

- If this codebase already contains 3 places where a similar module/change has been added, does your 4th change warrant doing in a different style? Are you committing for the other 3 too or are you just being a passenger for this one feature?

- What will be the cost of removing this module you are adding? Can we reduce the necessary churn it to removing 2 files (module + module test) from the code repository? and have nothing break?

- How many jumps from module to module (or function to function) will someone have to do to understand a specific flow in its entirety?

- Does the API surface of this module map well onto the underlying system one level down that it is driving?

Case study: if you ever wondered why so many have problems with Redux, try to size the codebases using Redux that you have seen against this list of questions:

- How hard will it be to remove this reducer+actions+dispatch functions if we want to get rid of them?

- How much indirection has to be followed to read this UX flow start-to-finish?

- Is the use of Redux state coherent with the use of local state?

Questions map to costs

In effect, when we bikeshed over these questions, we optimize for two very specific costs of software to us:

- Cost of reading and understanding

- Cost of removal/rework

And these costs are also to the business, because they will be very apparent when features have to change, or when the teams need to scale. Let’s deal with those in order.

Cost of reading and understanding

The first one is essential, and also something that is not well covered either in vocational study (bootcamps) or in CS curricula - we spend way, way more time reading and understanding existing code than we do creating new code. We absolutely do not pay enough attention to making our code easier to understand. And making code easier to read and understand is directly coupled to those pesky “taste” and “style” issues we so so forbid each other from discussing. Just a small sampling of those:

- Longer identifiers (

max_widthinstead ofmw) - Identifiers hinting behavior or type (

maybe_userfor a nullable,body_strfor a string as opposed to “body abstraction from one of the libraries we use”) - Use of keyword arguments/named arguments over positional arguments (

insert(at: pos, item: it)overinsert(it, pos) - Use of standard language constructs over framework constructs (

prependoverActiveSupport::Concern) - Comments explaining any non-obvious behavior (

# S3 multipart part numbers are 1-based) - Metaprogramming / macro output examples next to macro code

And these questions - if you look close enough - are not of the variety “I like it more” - they are of the variety “we are not doing our job well because it will be harder for a new person to understand this system”.

If we follow the now-mainstream “make everyone feel nice” ideology, we are invariably getting to a situation where asking for these affordances becomes a social misstep.

Moreover: modern teams with high-paced delivery operate via very, very opaque socio-political streams. With how hard it is to “perform” in a modern enterprise getting the “code” right is actually the easy part! There is a whole battery of adverse effects of the modern workplace which are going to make it impossible for the same person to “own” the same module for any meaningful amount of time. But exactly because of these difficulties we should pay more attention. Even if the model of operation is “commit the module, have people get their promotion, have a reorg, be moved to the next feature” - someone is going to inherit this code and highly likely will have to deal with it in some way. Someone will carry your can. The faster our org chart iteration, the more important it is to make your material discoverable, readable, clear.

Cost of removal/rework

This is something we do not think about much at all, because “removing a piece of software never got anyone promoted” - just like “nobody got fired for choosing Java”. But it does provide tangible benefits, and does make iteration easier!

For example, in the last project I have worked on, we implemented idempotency keys. Despite two great articles on the topic existing - one from Brandur and another from Ilja - there was no good module for idempotency keys we could use off-the-shelf, so we had to roll our own. We had to go through 2 throwaway implementations before we found one that became idempo

This would have been considerably harder to do if our idempotency keys were managed from the various applications we have inside of our Rack wrapper application, and became very easy with just one line of middleware. To swapover from one implementation to another, we had to change 2 lines in our codebase. To remove an iteration which didn’t work, we had to delete 2 files and 2 directories (since we used modules, everything could be removed in one go).

Same for things where - if you squint well enough - you say “if we were aiming for the microservice architecture this module would be a service”. Why not make it a single module with one function? If the fashion for microservices stays, and the product you are working on becomes more successful, replacing a local function call with an RPC call will be easy. Going in the opposite direction will be much harder because the cost of removal of a microservice is higher (remember the bit about “delete 2 files”).

See also - Write code that is easy to delete, not easy to extend.

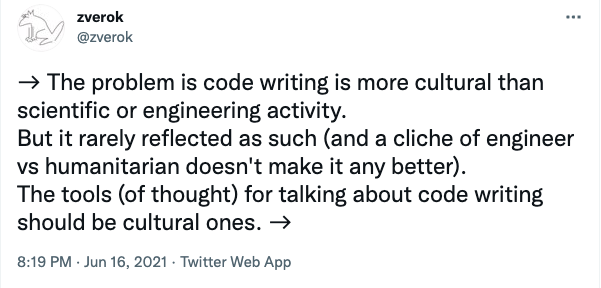

Good kind of bikeshedding is bikeshedding which optimizes for better communication and easy removal. Let me leave you with this quote by @zverok which should be printed on banners and hung on walls across all the offices where software gets worked on:

Truly the whole thread is magnificient - find it here

Thus: the bike shed should be green, because most bikesheds in our neighbourhood are green and because we regularly hire people who have never in their life seen a bike shed. And it must use keyword arguments. No argument about it.

For another great and considerate take on the topic - see Why We Argue: Style by Sandi Metz.