Turning your Apple Calendar into a time tracker

In the brave new world of self-employment one thing I found very important is getting a grip on time. In general, this turns out to be the biggest challenge for me personally - not having kids and no longer living with a partner I have way more free time than is customary for a 40+ year old, and it shows. And it is becoming more important to get a good understanding of both where the time gets spent, and how much of that time is billable.

In the past I used to use Noko for time tracking, but I found myself cooling down on it. I didn’t really enjoy having a subscription, the jobs I had to do were very sporadic and I no longer enjoyed using it. I’ve looked at a few time tracking packages but was generally put off by subscriptions, the perpetual “onlineness” of them all, and the fact that they were desperately selling to businesses, not consumers like myself. And – got to be frank about it – I am a sucker for not only local-first apps, but native apps.

And then an idea struck me: I am actually using the standard Apple Calendar, with online sync via iCloud, for my calendar needs. If I could add the entries to the calendar, and then tally them - this would give me a great time tracking solution, with the remaining work being generating the invoice from the tally of hours. And, despite Apple turning macOS into a prison of Duplo bricks year over year, there is still some automation available to make this work. So, shall we?

🧭 I am currently available for contract work. Hire me to help make your Rails app better!

The forgotten magic of OSA

Back when computers were personal, Facebook was non-existent and you could buy an application license and own it in perpetuity, macOS had a great feature embedded in it that quite a few people enjoyed: AppleScript. It was their answer to the VisualBasic scripting provided by Windows, and in some ways it was better than VB. The basics worked like this:

- Every application (and some system services) would expose an object model you could script against

- You would then use a peculiar language called AppleScript to address that object model

- The output of your script would not be something on standard output, but manipulations you would do in another application

In the brief period of macOS renaissance (what I would call the Avi Tevanian era) the model was expanded and the requirement to write things in AppleScript was dropped - the system became what is now known as the Open Scripting Architecture – or OSA, for short. You could talk to applications using any language of your choice, because the scripting functionality has gotten access to basic primitives exported by the operating system frameworks - so even with little effort by the developer, a world of interesting automations opened up.

And it was sorely needed. AppleScript was a language from a cohort of early 90-s programming languages which presumed that using “basic English” instead of language keywords would make the language more accessible. What it did instead was make it incredibly verbose. A hallmark of these languages was, surprisingly, using the to indicate that a variable contains a single value and is not a list. Behold:

set the clipboard to "Add this sentence at the end."

tell application "TextEdit"

activate --make sure TextEdit is running

make new paragraph at end of document 1 with data (return & the clipboard)

end tell

In this case the indicates that clipboard is a “universe-wide” singleton. I don’t generally adore Dijkstra’s statements on the practical side of programming, but I tend to agree with his views on natural language programming

Anyway, with the apparition of macOS X and its newer versions, AppleScript could finally be left behind and you could actually talk to the OSA backbone using any other language. For example, Apple would ship bindings to Cocoa and you could, at some point, do this:

require 'osx/cocoa'; include OSX

require_framework 'ScriptingBridge'

finder = SBApplication.applicationWithBundleIdentifier('com.apple.finder')

destination = finder.home.folders.objectWithName('Documents')

finder.desktop.files.get.each do |f|

f.moveTo_replacing_positionedAt_routingSuppressed(destination, nil, nil, nil)

end

All of that has died with the Duplo-ification and consumerization of the Mac, but one escape hatch has remained: you still can use JavaScript! And a relatively modern one at that, which is neat.

Getting at your calendar

The Calendar is just an application that is accessible by its name. We start with grabbing a specific calendar and having a prefix for the events we want to search for.

let Calendar = Application("Calendar")

let calendarName = "me";

let eventNamePrefix = "AcmeIndustries";

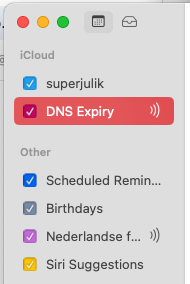

The calendarName is the name of the calendar visible in your Calendar.app in the pane:

Next comes the interesting part. We need to query for events in the calendar that have started after a certain point in time and that satisfy the name prefix. To do so, we need to use something called predicates - this is a weird Cocoa way of querying datasets. It has a few downsides - it has obtuse syntax, it is slow (I suspect that every extra predicate is a linear scan, making every added predicate a power increase in algorithmic complexity – which is going to be incredibly noticeable if you keep your calendar alive for years already). But it is workable, so let’s do some objc_msgsend by proxy of a proxy of a proxy:

let theCalendar = Calendar.calendars.whose({name: calendarName})[0]

let fromDate = new Date(2025, 4, 25)

let eventPredicate = theCalendar.events.whose(

{_and: [

{summary: { _beginsWith: eventNamePrefix }},

{startDate: { _greaterThan: fromDate}}

]

}

);

I am using theCalendar as a cheeky name owing to the AppleScript heritage. Note that we immediately do the postfix indexing for [0] - this is important. A predicate is just that - a predicate. Think about it as you would think about a prepared SQL query - the system has compiled it, but didn’t execute it yet. To execute the predicate you either call it (because, believe it or not, the thing you get back from whose is both a function and an indexable object!) or index into it.

Then, for our events, we need a compoind predicate. In this case we want all events whose summary - which is the title of the event - begins with our prefix. Why an underscore is needed at the start - I don’t know, but in general the OSA thing is somewhat janky, and I tend to just accept it for what it is. For the start date we apply a greaterThan condition which is going to add a cutoff to our search, that speeds up our predicate considerably.

Next, we resolve our predicate - which returns us handles to Event objects. Those objects are also functions and should be called to be resolved! But it does work. And, as a bonus, JS syntax supported by OSA is fairly modern - it has a builtin JSON module, let, const and object shorthands.

let pertinentEvents = eventPredicate();

for (var evtResolver of pertinentEvents) {

let evtHandle = evtResolver();

let evt = {

uid: evtHandle.uid(),

summary: evtHandle.summary(),

startDate: evtHandle.startDate().toISOString(),

endDate: evtHandle.endDate().toISOString(),

};

console.log(JSON.stringify(evt));

}

console.log(JSON.stringify(materializedEvents));

You may notice that I deliberately keep this script short and make it use console.log() to output the events in a digestible JSON format (technically, our output is going to be JSONlines) - that is for a good reason.

OSA is slow. Very, very slow. The error messages it outputs are obtuse and often somewhat cryptic. There is no proper debugging (there is some, but it is also pretty bad), and the fact that you need to call a property of an object instead of accessing it directly adds to the confusion. Therefore, I vastly prefer retrieving all the data I need, outputting it in some common format, and then doing the processing in an environment with a better DX.

We save our script into extract-events.osa.js and then we can run it using osascript from the Terminal, like so:

$ osascript -l JavaScript extract-events.osa.js

It is also a good idea to allow our script to accept arguments. To do that, we need to wrap our entire script into a run function - it will get the ARGV array as its argument:

function run(argvArray) {

let [calendarName, eventNamePrefix, fromDateStr] = argvArray;

let fromDate = new Date(fromDateStr)

let Calendar = Application("Calendar")

let theCalendar = Calendar.calendars.whose({name: calendarName})[0]

let eventPredicate = theCalendar.events.whose(

{_and: [

{summary: { _beginsWith: eventNamePrefix }},

{startDate: { _greaterThan: fromDate}}

]

}

);

// Resolve the array

let totalHours = 0;

let pertinentEvents = eventPredicate();

let materializedEvents = [];

for (var evtResolver of pertinentEvents) {

let evtHandle = evtResolver();

let evt = {

uid: evtHandle.uid(),

summary: evtHandle.summary(),

startDate: evtHandle.startDate().toISOString(),

endDate: evtHandle.startDate().toISOString(),

};

console.log(JSON.stringify(evt));

}

}

and we pass our arguments in order:

$ osascript -l JavaScript extract-events.js superjulik "AcmeIndustries" 2025-08-01

and we get some terminal output:

$ osascript -l JavaScript extract-events.osa.js superjulik "AcmeIndustries - " 2025-08-01

{"uid":"43804A58-6207-4D22-A3A1-B1433DA1CB03","summary":"AcmeIndustries - Processing Flow Rework","startDate":"2025-08-04T15:45:00.000Z","endDate":"2025-08-04T15:45:00.000Z"}

{"uid":"CE846421-4246-4BBB-B4A7-855CCEC54286","summary":"AcmeIndustries - Generative flow bug investigation","startDate":"2025-08-12T21:30:00.000Z","endDate":"2025-08-12T21:30:00.000Z"}

{"uid":"0126979A-BCF3-4627-96A6-6B3D7ECDCFB8","summary":"AcmeIndustries - Processing Flow","startDate":"2025-08-17T17:00:00.000Z","endDate":"2025-08-17T17:00:00.000Z"}

{"uid":"D04253FB-33DC-425A-9E5D-28E6F123616F","summary":"AcmeIndustries - Processing Flow refactor","startDate":"2025-08-21T11:30:00.000Z","endDate":"2025-08-21T11:30:00.000Z"}

{"uid":"6391A949-4147-4F04-AE78-28C4B635E379","summary":"AcmeIndustries - Processing Flow Rework","startDate":"2025-08-21T14:00:00.000Z","endDate":"2025-08-21T14:00:00.000Z"}

{"uid":"8A96EEA0-57D0-43E1-90A4-0C6FB940B2C3","summary":"AcmeIndustries - Processing Flow Rework","startDate":"2025-08-21T15:30:00.000Z","endDate":"2025-08-21T15:30:00.000Z"}

{"uid":"7E0B00C3-C383-4360-9906-D70B584E15B2","summary":"AcmeIndustries - Processing Flow","startDate":"2025-08-21T22:00:00.000Z","endDate":"2025-08-21T22:00:00.000Z"}

Tedious, painful - but it works. And goes through… the official channels.

It also takes nearly 2 minutes to run. 2 minutes on an M1 MacBook Pro to recover 7 events with what amounts to a prefix search and an integer comparison. From data that is sitting there on the internal SSD (and maybe - even in memory).

Now with 100 times less Official Framework Scripting Garbage

You wouldn’t expect that I’d stop there though, wouldn’t you? After all, that Apple Calendar data ought to also be stored… somewhere on the computer. And it ought to be stored in some format that allows faster and more optimized access to things than this… abomination.

What if that format is a SQLite database?..

$ lsof | grep Calendar | grep sql

calaccess 1086 julik txt REG 1,18 32768 42610 /Users/julik/Library/Group Containers/group.com.apple.calendar/Calendar.sqlitedb-shm

calaccess 1086 julik 4u REG 1,18 8454144 42582 /Users/julik/Library/Group Containers/group.com.apple.calendar/Calendar.sqlitedb

calaccess 1086 julik 5u REG 1,18 173072 42608 /Users/julik/Library/Group Containers/group.com.apple.calendar/Calendar.sqlitedb-wal

calaccess 1086 julik 6u REG 1,18 32768 42610 /Users/julik/Library/Group Containers/group.com.apple.calendar/Calendar.sqlitedb-shm

dataacces 1240 julik txt REG 1,18 32768 42610 /Users/julik/Library/Group Containers/group.com.apple.calendar/Calendar.sqlitedb-shm

dataacces 1240 julik 8u REG 1,18 8454144 42582 /Users/julik/Library/Group Containers/group.com.apple.calendar/Calendar.sqlitedb

dataacces 1240 julik 9u REG 1,18 8454144 42582 /Users/julik/Library/Group Containers/group.com.apple.calendar/Calendar.sqlitedb

dataacces 1240 julik 10u REG 1,18 32768 42610 /Users/julik/Library/Group Containers/group.com.apple.calendar/Calendar.sqlitedb-shm

dataacces 1240 julik 11u REG 1,18 8454144 42582 /Users/julik/Library/Group Containers/group.com.apple.calendar/Calendar.sqlitedb

dataacces 1240 julik 16u REG 1,18 173072 42608 /Users/julik/Library/Group Containers/group.com.apple.calendar/Calendar.sqlitedb-wal

com.apple 17267 julik txt REG 1,18 32768 2576443 /Users/julik/Library/Containers/com.apple.CalendarWeatherKitService/Data/Library/HTTPStorages/com.apple.CalendarWeatherKitService/httpstorages.sqlite-shm

com.apple 17267 julik 3u REG 1,18 4096 2576439 /Users/julik/Library/Containers/com.apple.CalendarWeatherKitService/Data/Library/HTTPStorages/com.apple.CalendarWeatherKitService/httpstorages.sqlite

com.apple 17267 julik 4u REG 1,18 32992 2576442 /Users/julik/Library/Containers/com.apple.CalendarWeatherKitService/Data/Library/HTTPStorages/com.apple.CalendarWeatherKitService/httpstorages.sqlite-wal

com.apple 17267 julik 5u REG 1,18 32768 2576443 /Users/julik/Library/Containers/com.apple.CalendarWeatherKitService/Data/Library/HTTPStorages/com.apple.CalendarWeatherKitService/httpstorages.sqlite-shm

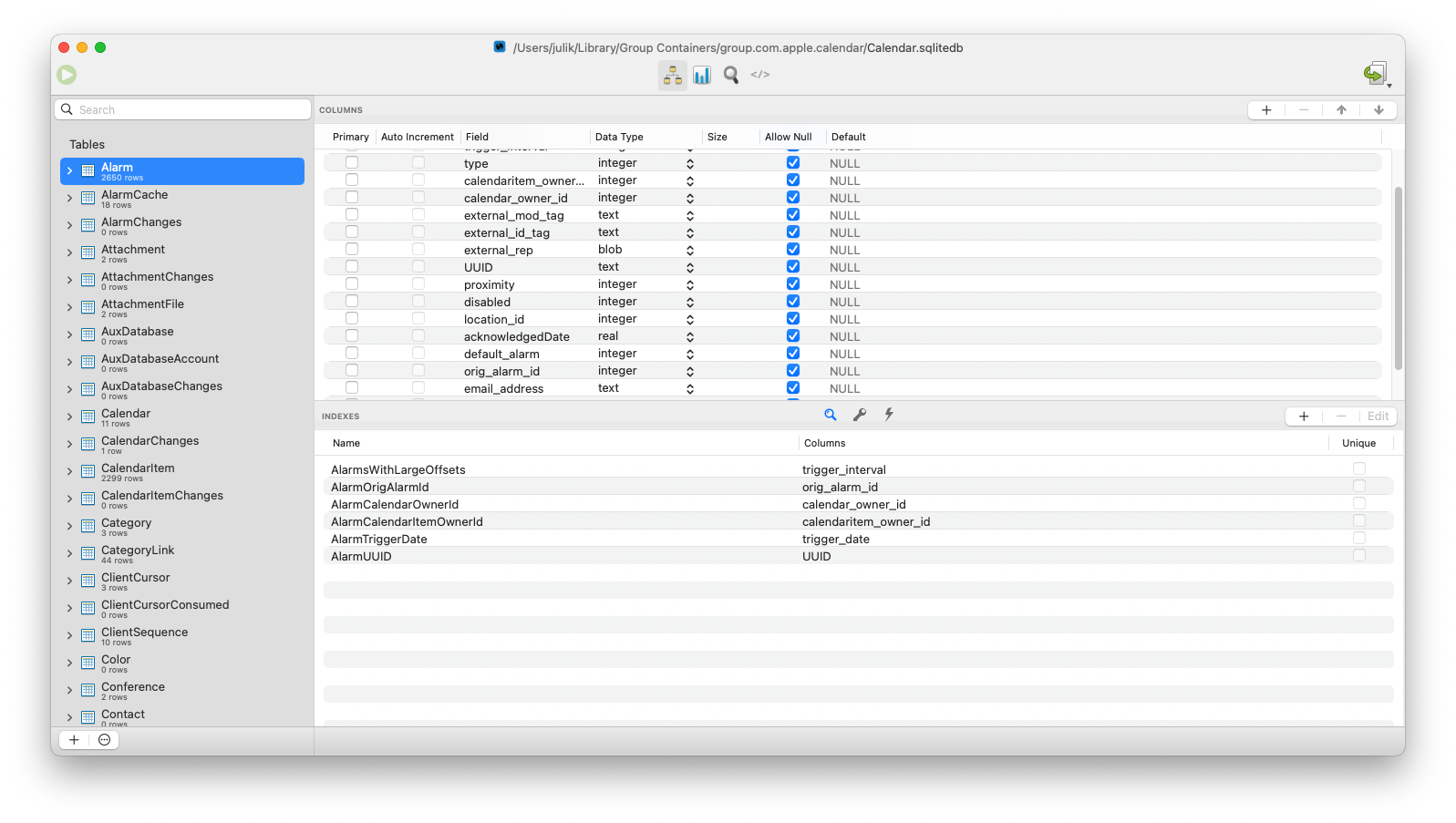

Would you look at that! So there is apparently a SQLite database with our calendar data! Let’s take a closer look:

For what we need to accomplish, we only need the Calendar and CalendarItem tables. Let’s do a query!

SELECT * FROM CalendarItem WHERE start_date > (strftime('%s', '2025-07-01') - 978307200) AND end_date < (strftime('%s', 'now') - 978307200)

What is this weird 978307200 you would ask? Well… the fields in the database are stored as epoch seconds. But - not from UNIX epoch, but from some… weird macOS epoch - namely, 2001-01-01 00:00:00 UTC - which is, apparently, a CoreData standard. The fixed offset converts our input time value into a value that can be compared against in that CoreData epoch.

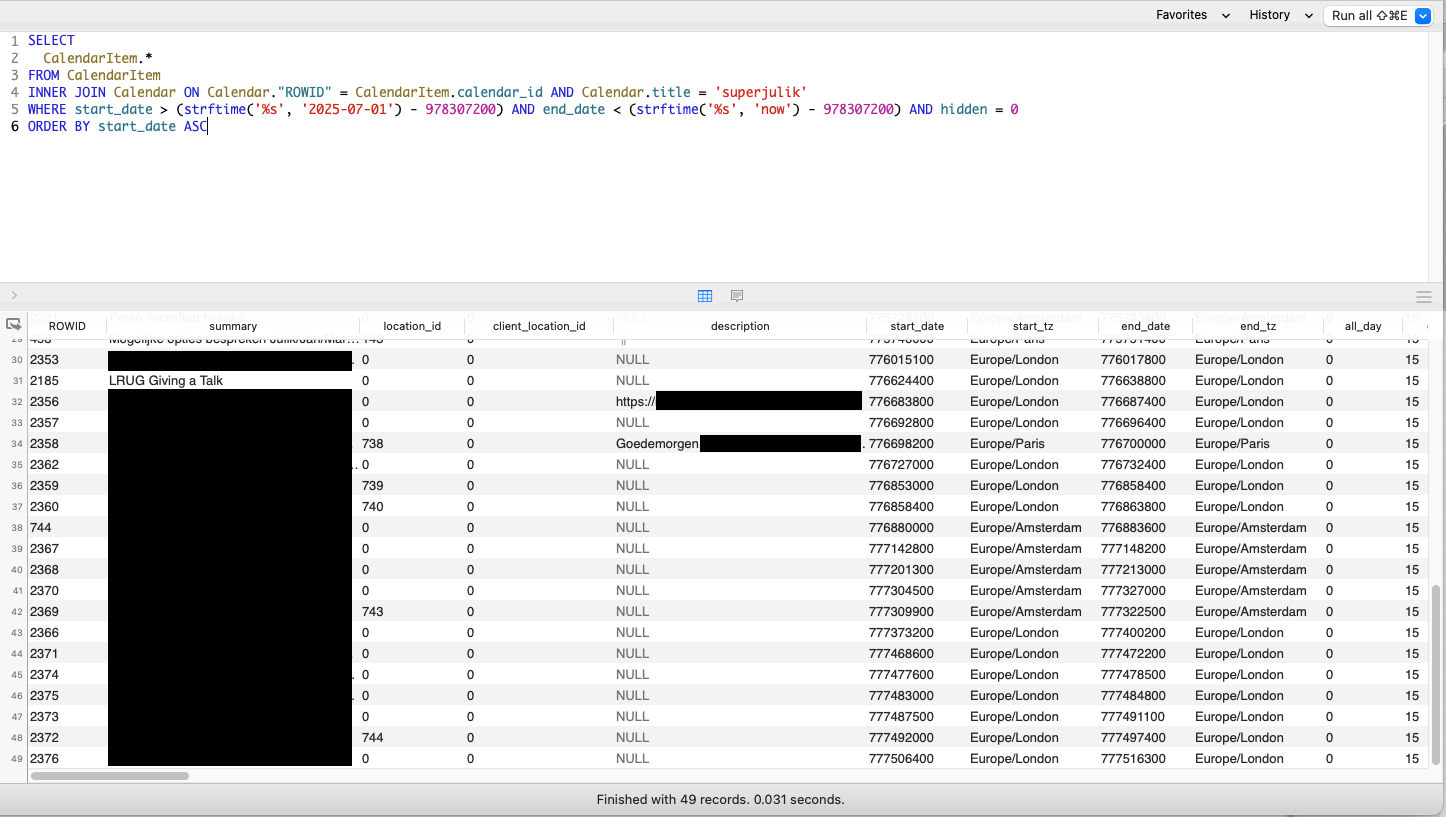

That query takes… 37 milliseconds and returns 50 records for my calendar, which is not bad compared to the scripting access to an even smaller subset of records which takes 120 seconds. We also want to query for the correct calendar:

SELECT

CalendarItem.*

FROM CalendarItem

INNER JOIN Calendar ON Calendar."ROWID" = CalendarItem.calendar_id AND Calendar.title = 'superjulik'

WHERE start_date > (strftime('%s', '2025-07-01') - 978307200) AND end_date < (strftime('%s', 'now') - 978307200)

ORDER BY start_date ASC

and finally, we add our clause for the event title:

SELECT

CalendarItem.*

FROM CalendarItem

INNER JOIN Calendar ON Calendar."ROWID" = CalendarItem.calendar_id AND Calendar.title = 'superjulik'

WHERE

start_date > (strftime('%s', '2025-07-01') - 978307200) AND

end_date < (strftime('%s', 'now') - 978307200) AND

summary LIKE 'Acme%'

ORDER BY start_date ASC

Since we have access to all the interesting data, we can easily tally up the hours spent on Acme-related projects now:

WITH tracked_items AS (

SELECT

CalendarItem.*

FROM CalendarItem

INNER JOIN Calendar ON Calendar."ROWID" = CalendarItem.calendar_id AND Calendar.title = 'superjulik'

WHERE

start_date > (strftime('%s', '2025-06-01') - 978307200) AND

end_date < (strftime('%s', 'now') - 978307200) AND

summary LIKE 'Acme%'

ORDER BY start_date ASC

) SELECT SUM(end_date - start_date) / 60 / 60 AS total_hours FROM tracked_items

and we are done! I would recommend opening the database in readonly mode though since it is likely managed by all sorts of CoreData magic. And - of course - you can add your own notes into the “Description” of your calendar events and examine them in your data collection script.

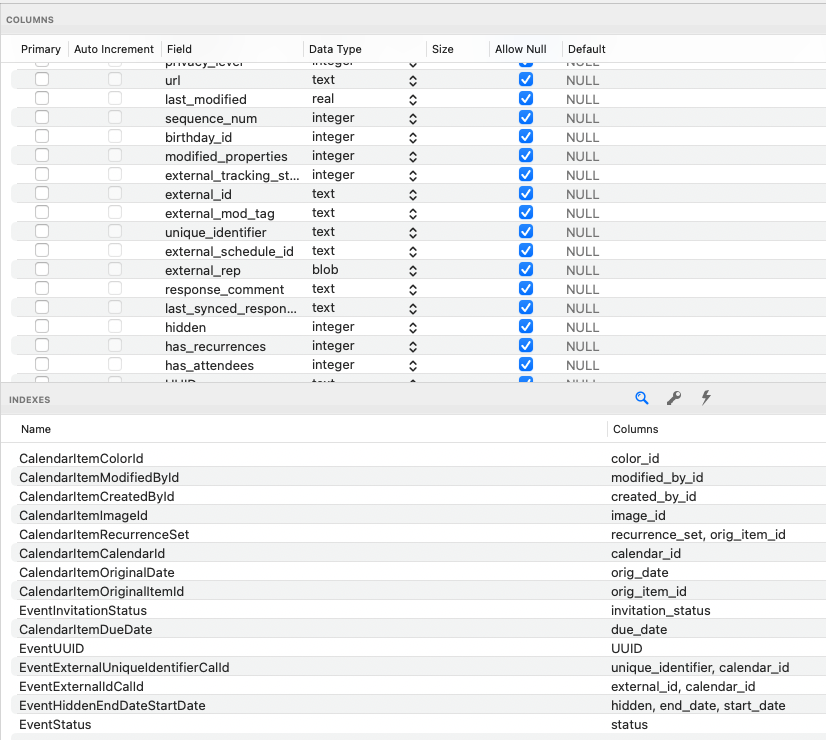

If you have thousands of calendar items or the SELECT turns out to be slow - take a look at the structure of the CalendarItem table:

There is an index called EventHiddenEndDateStartDate that can be used but to make use of it you need to add hidden = 0 to your query conditions (and possibly use a WITH MATERIALIZED).

One caveat is that if you want to do something to that data - I would not muck about with CoreData-managed databases and store “my” data elsewhere, using the ROWID as external reference. Don’t forget that you can also connect that database to yours by opening it as an additional data source.