On the way to step functions: geneva_drive

This is the concluding article in the series On the Way to Step Functions - you will find the other articles linked below:

- On the way to step functions: Part 1

- On the way to step functions: Part 2

- On the way to step functions: Part 3

We have established a few important points so far.

- The spirit, the desiderata of durable execution comes from the desire to have marshalable stacks - which are unachievable.

- Second-best option are workflows, which are actually DAGs under the hood.

- The DAG definition and the code inside the nodes are two separate worlds with different semantics.

- Systems that pretend they are one body of execution will make you hurt.

So: how do we apply these insights to Rails? Enter geneva_drive.

🧭 I am currently available for contract work. Hire me to help make your Rails app better!

Why “geneva drive”?

A Geneva drive is a gear mechanism that converts continuous rotary motion into intermittent rotary motion. It is the mechanism that makes film projectors advance one frame at a time - continuous energy in, discrete steps out. Which is exactly what we want from our workflow engine: the relentless progression of time, converted into discrete, controlled steps.

Besides, the clockwork theme is already with us thanks to Xavi and zeitwerk.

What is the “right API” then?

It may seem trite, but it should answer my basic requirement of intuitiveness – it should be exactly like other things we already know.

That implies:

- Using existing, integrated and known dependencies and subsystems

- Utilizing concepts which are immediately recognizable - and malleable!

- Adding just enough sugar to enable new functionality

And there was an API like this already! It was heya from Honeybadger. Observe a Heya campaign:

class OnboardingCampaign < ApplicationCampaign

step :first, subject: "First subject"

step :second, subject: "Second subject"

step :third, subject: "Third subject"

end

If you have used Rails long enough, this should look very self-explanatory - and, dare I say, intuitive.

And the story could have even ended with Heya, except that

- That

stepaccepts options forActionMailer, and nothing else. It does not accept blocks. - You can’t even have instance methods used by steps

- The campaign is a weird-ish “anemic” class that you can’t call anything much on

- State is packaged in a very opaque manner

- A lot of sugar is geared deliberately towards drip campaigns

But the rest was near damn perfect! Thus the idea: let’s take this API, remove everything underneath and everything that is too email-specific. And repurpose it towards generic, discrete workflows. Thus: geneva_drive.

The hero pattern

The heart of a Rails application is the domain model - and model entities it consists of. Heya exists in some nebulous realm where there is no stable connection between the models of the application and the campaign - except for arbitrary method calls. But actual workflows always have a key model that they operate on, or in service of. Observe:

- A

PaymentWorkflowlikely manages states and evolutions of aPayment - An

OnboardingWorkflowis certainly concerned with someUserorAccount - An

ArchivingWorkflowis likely concerned with aProjector aTenant

Every workflow will likely need a subject - in geneva_drive, we call this the “hero”. And because workflows are actual DB-persisted Rails models - it is a polymorphic association that ties the workflow to any ActiveRecord model:

class TransferWorkflow < GenevaDrive::Workflow

alias_method :transfer, :hero

step :initiate do

# ...

end

end

Why “hero”? Because in any story, there is a protagonist. The workflow is not the protagonist - the workflow is the narrative arc that the protagonist goes through. The transfer, the user, the order - that is the hero. The workflow describes the journey.

This is not merely philosophical navel-gazing. The hero pattern has practical consequences. A workflow is not only uniquely identified by its primary key, but can also be uniquely identified by the tuple {hero_type, hero_id, workflow_type}. You cannot have two TransferWorkflow instances for the same Transfer that are in progress - and that is enforced at the level of database constraints. You can have a TransferWorkflow and an AuditWorkflow for the same Transfer, though.

TransferWorkflow.for_hero(transfer) # => finds or initializes the workflow

transfer.transfer_workflow # => if you've set up the association

This gives you something that ActiveJob fundamentally cannot provide: stable identity. A job is a ticket to be processed. A workflow is an entity with state.

The eigenclass revelation

Here is a geneva_drive workflow:

class TransferWorkflow < GenevaDrive::Workflow

alias_method :transfer, :hero

step :initiate, on_exception: :reattempt! do

result = client.transfer(

amount: transfer.amount,

idempotency_key: Digest::SHA1.hexdigest(transfer.to_param)

)

transfer.update!(external_id: result.id, state: "in_progress")

end

step :poll, on_exception: :reattempt! do

status = client.get_transfer(transfer.external_id)

if status.ok?

transfer.update!(state: "done")

elsif status.in_progress?

reattempt! wait: 5.seconds

elsif status.rejected?

transfer.update!(state: "failed")

else

pause!

end

end

end

Look at this carefully. Where does the DAG definition live? Where does the imperative code live? If you are used to ActiveRecord’s meta-programming, the answer will be obvious.

The step :initiate call happens at class definition time. When Ruby parses this file, it evaluates the class body, which includes the step method calls. These calls register steps in a class-level data structure. This is the eigenclass context - the singleton class of TransferWorkflow, where class methods and class-level state live.

The block passed to step - the do ... end part - is not evaluated at class definition time. It is stored, to be executed later in the context of a workflow instance. When we call workflow.perform_next_step!, the block runs with self being the workflow instance, with access to hero, to pause!, to reattempt!.

This is not an accident. This is the perfect mapping of the two-worlds problem onto Ruby’s object model - and moreover, to something we are used to in Rails.

The eigenclass (class body) is your DAG. It is declarative. It runs once, at load time. It defines structure: what steps exist, what order they come in, what their options are. Like a Nuke script defining nodes and connections. Like Terraform’s HCL defining resources and their dependencies.

Instance methods (step blocks) are your nodes. They are imperative. They run at execution time, potentially many times, on different machines, minutes or days apart. They do stuff: call APIs, update records, send emails. Like the C++ code inside a Nuke node. Like the Go code inside a Terraform provider.

Ruby’s object model gives us this separation for free. We do not need a special DSL. We do not need to invent new abstractions. We just use the language the way it was designed to be used. The class body runs once and defines structure. Instance methods run later and do work.

The ActiveRecord advantage

Geneva_drive workflows are ActiveRecord models. Not “backed by ActiveRecord” or “persisted to ActiveRecord” - they are ActiveRecord models, using single-table inheritance:

class GenevaDrive::Workflow < ApplicationRecord

# ...

end

class TransferWorkflow < GenevaDrive::Workflow

# ...

end

This has enormous practical benefits.

Queryability. You can do TransferWorkflow.performing.where(created_at: 1.hour.ago..) and find workflows that have been stuck for an hour. You can do User.joins(:onboarding_workflow).where(workflows: {state: :finished}) to find users who completed onboarding. This is not possible with ActiveJob, where jobs are opaque blobs in a queue.

Associations. Your User model can has_one :onboarding_workflow, as: :hero. Your workflow can belongs_to :hero, polymorphic: true. Rails associations just work, because workflows are just models.

Transactions. When a step runs, it can participate in the same transaction as your business logic. No distributed transactions, no eventual consistency headaches. Just normal Rails database operations.

No external dependencies. Geneva_drive needs nothing beyond your existing Rails stack. No Redis (unless you are already using it for ActiveJob), no Kafka, no gRPC, no Zookeeper. The database is your single source of truth. This is not a limitation - this is a feature. Every external dependency is a failure mode, is an extra system to learn, to monitor, to update. It is more stuff.

Waiting is easy

Want to have a “burndown” process for wallet reclaim that takes 6 months? That’s very easy with geneva_drive. Since steps run asynchronously and are scheduled via your background jobs, arbitrary waits are possible. Moreover: those waits happen at the level of the DAG, not in your step code - so their clock semantics can be cleanly defined:

class WalletReclaimWorkflow < GenevaDrive::Workflow

step :send_warning

3.times do # Send 3 warnings, spaced 30 days

step(wait: 30.days) { send_warning }

end

step(wait: 24.hours) { send_warning }

step :perform_wallet_reclaim

end

Because we don’t try to pretend these waits are sleep() calls they fit naturally into the calling convention.

State machines within state machines

A workflow has states: ready, performing, finished, canceled, paused. These are enforced by a state machine that validates transitions. You cannot go from finished to performing. You cannot call cancel! on a workflow that is already canceled.

But steps also have states. A StepExecution record - which represents a single attempt to run a step - can be scheduled, in_progress, completed, or failed. When you call reattempt! wait: 5.minutes, a new StepExecution is created with state scheduled, and an ActiveJob is enqueued to run it in 5 minutes.

This is important: retrying a step creates a new execution record. It does not mutate the existing one. This means you have an audit trail of every attempt. You can see that step :poll was attempted 47 times over 3 hours before finally succeeding. You can query for workflows whose current step has failed more than 5 times.

The step execution model also solves idempotency for free. When the PerformStepJob runs, it locks the step execution record and checks its state. If the state is not scheduled, the job exits early. This prevents double-execution if the job gets enqueued twice, or if the worker crashes and the job gets retried.

Flow control as a first-class concept

Inside a step block, you have access to flow control methods:

step :check_status do

status = api.get_status(transfer.external_id)

case status

when :pending then reattempt! wait: 30.seconds

when :approved then nil # proceed to next step

when :rejected then cancel!

when :suspicious then pause!

end

end

reattempt! wait: duration- retry this step after a delayskip!- skip this step and proceed to the nextpause!- pause the workflow for manual interventioncancel!- abort the workflow entirelyfinish!- complete the workflow early, skipping remaining steps

These are not magic. They are just Ruby throws with some additional stack information passed up that the executor catches and handles. When you call reattempt!, the step block throws a :reattempt - it’s that mundane. The executor catches it, creates a new scheduled step execution, enqueues a job, and returns. No special runtime, no coroutines, no async/await, no fibers, no IO.select or reactors. Just throw.

And you don’t need to return when controlling flow this way - unlike in ActionController, because that return would just be extra ceremony. If you want to jmp you should have the latitude to jmp, no questions asked.

Transactional boundaries

One of the trickiest parts of workflow engines is getting the transactional boundaries right. You want your business logic to be transactional. But you do not want to hold a database lock while calling an external API that might take 30 seconds.

Geneva_drive is explicit about this. Database transactions are held only during:

- Checkout - locking the workflow and step execution, validating state

- Scheduling - creating the next step execution record

- Recording outcomes - updating the step execution state after completion

Your step code runs outside of these transactions. When you call transfer.update!(state: "in_progress") inside a step, that is a separate transaction from the framework’s bookkeeping. This means your API calls do not hold locks. Your bulk database operations do not block the workflow machinery.

If you need your step logic to be transactional with the framework’s state updates, you can wrap it yourself:

step :critical_update do

ActiveRecord::Base.transaction do

transfer.update!(state: "processed")

hero.save! # triggers workflow state update

end

end

But in most cases, you do not need this. The step execution state machine provides the guarantees you need. If your step crashes after updating the transfer but before the framework records completion, the step will be retried - and your step logic should be idempotent enough to handle that.

How does scheduling work?

Scheduling in geneva_drive is a bit tricky, but very simple once you peel away the sugar. Rails apps, historically, do not come with a good scheduler. This has a number of reasons, one of them being that most Rails apps are distributed systems by default, but the traditional (read: “We Have An Experienced Platform Team”) approach was to outsource scheduling to an orchestrator, like Kubernetes, once your number of machines exceeds 1. And otherwise it would be some kind of cron job or systemd.

The situation has changed with recent versions of ActiveJob, though. With the addition of the set(wait:) option (and the scheduled_at job param) it became possible to schedule an ActiveJob arbitrarily far into the future. While there were severe limitations to this - like the SQS’s “900 seconds” max delay - or storage constraints, like Redis (for Sidekiq) being “ephemeral” storage - this enabled scheduling patterns that would satisfy the main constraints one usually needs met:

- There is at-least-once execution

- A consistent clock source is used (or at least available) for scheduling times

geneva_drive uses a very simple setup for this, which accommodates the fact that ActiveJob adapters may be, under certain conditions, somewhat flaky. When you schedule a step to run, a StepExecution record gets inserted into your database. That record is guaranteed to have committed before anything gets prepared for actually executing the step. Then, an ActiveJob gets enqueued, with roughly the following shape:

class StepJob < ActiveJob::Base

def perform(step_execution_id)

# ...

end

end

The job then gets enqueued setting the wait_until option:

StepJob.set(wait_until: step_execution.scheduled_at).perform_later(step_execution)

This is very small, very simple and robust. Moreover, it allows meaningful recovery! Imagine your entire job queue storage got wiped (Redis down and your Experienced Platform Team™ has not configured proper Redis backups or failover), for example? That’s no big deal. Find all step executions which are pending and re-schedule them:

GenevaDrive::StepExecution.pending.find_each do |step_execution|

GenevaDrive::PerformStepJob.set(wait_until: step_execution.scheduled_at).perform_later(step_execution)

end

The ActiveJob is very small for a reason: exactly because ActiveJobs are opaque, not cleanly identifiable and work very differently depending on the adapter, the job is just the “finger that pulls the trigger”. The rest of the operation is backed by your transactional database and models, which are known - and designed - to be robust, with proper consistency and durability guarantees.

Yes, this does result in some latency (in production we do see about 100ms between steps for everything to get committed-then-recalled), but that setup gives you a lot of stability and consistency. And makes the entire workflow recoverable should your ActiveJob queue throw a wobbly!

Idempotency remains your responsibility

This is worth emphasizing: geneva_drive does not magically make your code idempotent. If your step calls PaymentGateway.charge(user) and crashes after the charge succeeds but before recording completion, the retry will charge the user again. That is your bug, not the framework’s.

The framework gives you tools to help. The hero is always available, so you can store idempotency keys on it:

step :charge do

idempotency_key = Digest::SHA1.hexdigest("charge-#{transfer.id}-#{step_execution.id}")

PaymentGateway.charge(user, idempotency_key: idempotency_key)

end

The step_execution is also available, giving you a unique identifier for this specific attempt. But you have to use these tools. The framework cannot know which of your operations have side effects and which do not.

This is the same responsibility you have with any durable execution system. Temporal does not magically make your activities idempotent either - it just replays them if they were not recorded as complete. The difference is that geneva_drive does not pretend otherwise.

Testing with time travel

A workflow that waits 10 days between steps is hard to test. And 10 days is hardly the limit: some workflows are designed to run over months. You do not want your test suite to actually wait 10 days. So a little time-travel to the tune of ActiveSupport::TestCase is very much needed - and it’s there!

class TransferWorkflowTest < ActiveSupport::TestCase

include GenevaDrive::TestHelpers

test "workflow completes after polling" do

transfer = transfers(:pending)

workflow = TransferWorkflow.for_hero(transfer)

# This will fast-forward through all the `wait:` durations

speedrun_workflow(workflow)

assert workflow.finished?

assert transfer.done?

end

end

The speedrun_workflow helper runs the workflow synchronously, using travel_to to skip past any scheduled delays. Your 10-day workflow completes in milliseconds. This is only possible because the workflow definition is declarative - we can introspect the structure and know exactly when each step is scheduled to run.

What geneva_drive does not do

Geneva_drive is deliberately constrained in scope. It is a scheduling and state-machine layer, not a distributed transaction coordinator. Here is what it does not provide:

Sagas and rollback. If step 3 fails and you need to undo steps 1 and 2, that is your responsibility. You can implement compensation logic in your step code, but the framework does not have a declarative rollback mechanism.

Mid-step suspension (yet). You cannot pause a step halfway through and resume from that point. Steps are atomic units of work. If you need fine-grained suspension, break your work into smaller steps.

Parallel execution (yet). The current version executes steps sequentially. Fork-and-join is on the roadmap, but not implemented. If you need parallelism today, you can spawn separate workflows and wait for them in a polling step. Or combine geneva_drive with scatter_gather.

Admin UI (in the base version). The open-source version is the workflow engine. The geneva_drive admin UI is already being tested inside of select products - and, trust me, it is neat - but it likely is going to be a paid offering.

These are conscious trade-offs. Every feature adds complexity, and complexity adds bugs. Geneva_drive aims to do one thing well: provide a durable, queryable, ActiveRecord-native workflow engine. It is not trying to be Temporal.

The bigger picture

If you have read this far, you might be wondering: is all this really necessary? Cannot we just use ActiveJob with some retry logic?

You can. And for many use cases, you should. If your workflow is “send email, done” - you do not need geneva_drive. If your workflow is “process payment, wait for webhook, update status, wait 10 days, send reminder” - you will have a bad time with ActiveJob. In fact, if you already do the above - you are likely to be having a bad time already. The pain is not technical complexity. The pain is opacity. With pure ActiveJob, you cannot answer: “how many payment workflows are stuck in the polling phase?” You cannot answer: “what is the average time between step 2 and step 3?” You cannot answer: “which users started onboarding but never finished?”

These are business questions, and they require your workflows to be first-class entities with queryable state. Moreover, that state is not packaged into the ActiveJob blob, and there is just one workflow - clearly identifiable, queryable, at your fingertips. That is exactly what we do with durable execution. The continuous churn of background job processing gets converted into discrete, observable, queryable workflow states. One frame at a time.

Contenders

There are other approaches to this problem in the Rails ecosystem, and they deserve consideration. Each makes different trade-offs, and understanding those trade-offs helps clarify why geneva_drive exists.

ductwork

Ductwork is a well-designed gem for building data pipelines. Its API is fluent and expressive:

class EnrichUserDataPipeline < Ductwork::Pipeline

define do |pipeline|

pipeline.start(QueryUsersRequiringEnrichment)

.expand(to: LoadUserData)

.divide(to: [FetchDataFromSourceA, FetchDataFromSourceB])

.combine(into: CollateUserData)

.chain(UpdateUserData)

.collapse(into: ReportSuccess)

end

end

The design is solid for its intended purpose: ETL jobs, data enrichment, batch processing. Data flows between steps as return values, and the expand/divide/combine/collapse primitives handle fan-out and fan-in elegantly.

However, it is optimized for a different problem than business workflows. In ductwork, there is no persistent “subject” of the workflow - data flows through pipes. This is perfect when you are processing a batch of records, but less ideal when you want to say “show me all payment workflows that are stuck” or “what is the state of this user’s onboarding?” The pipeline model does not naturally support querying workflow state by the entity being operated on.

The requirement that return values be JSON-serializable also reveals a different design philosophy. In ductwork, steps communicate through their outputs. In geneva_drive, steps communicate through the hero - the shared, persistent subject that every step can read and modify. Neither approach is wrong; they serve different needs.

I do have severe reservations against the API design here (like using Ruby modules as arguments, or trying to construct a lodash alternative inside Rails) but those are questions of taste, rather.

ActiveJob::Continuation

Rails 8 introduced ActiveJob::Continuation, which adds step-based execution to ActiveJob:

class PaymentJob < ApplicationJob

include ActiveJob::Continuation

def perform(payment)

step :authorize do

# ...

end

step :capture do

# ...

end

end

end

This is a pragmatic addition to ActiveJob that solves real problems. If you are already using ActiveJob and need basic step tracking, it is a reasonable choice with minimal ceremony.

The design difference from geneva_drive is subtle but significant: the step calls happen at execution time, inside perform. Every time the job runs, it re-evaluates which steps exist. This means you cannot introspect the workflow structure at class level - you would need to run the job to discover its steps. For simple linear workflows this is rarely a problem. For complex workflows where you want tooling to understand the structure without executing it, it becomes a limitation. It is exactly the issue of mixing the DAG and the nodes inside of one body of code. There is no steps class method in ActiveJob::Continuation that you can use to introspect your steps. There absolutely is one in geneva_drive.

ActiveJob::Continuation also inherits ActiveJob’s identity model: jobs are tickets to be processed, not entities with persistent state. You cannot easily query “all payment jobs that completed step 1 but not step 2” because that information lives in the job’s serialized arguments, not in a queryable form.

GoodJob batches

GoodJob is an excellent ActiveJob backend, and its batch feature provides a way to group related jobs:

batch = GoodJob::Batch.enqueue(on_finish: BatchCallbackJob) do

User.find_each do |user|

SyncUserJob.perform_later(user)

end

end

Batches solve a real coordination problem: “run these N jobs and do something when they all complete.” This is genuinely useful for fan-out/fan-in patterns.

However, batches are not workflows. A batch is a collection of independent jobs with a completion callback. There is no sequential step progression, no conditional branching based on step results, no “wait 10 days then do the next thing.” Batches answer “did all these jobs finish?” but not “what step is this workflow on?” or “why did this workflow pause?”

You could build workflow-like behavior by chaining batches through callbacks, but at that point you are fighting the abstraction rather than using it. GoodJob batches are excellent at what they do; they are just solving a different problem than durable workflows. Use them for that problem!

Temporal

Temporal is the heavyweight champion of durable execution. It provides strong guarantees, sophisticated failure handling, and scales to enormous workloads.

def payment_workflow(payment_id)

authorize_result = workflow.execute_activity(:authorize_payment, payment_id)

if authorize_result.success?

workflow.execute_activity(:capture_payment, payment_id)

end

workflow.sleep(10.days)

workflow.execute_activity(:finalize_payment, payment_id)

end

For organizations with dedicated platform teams and complex distributed systems, Temporal is worth serious consideration. Its replay-based execution model is clever: the workflow function runs from the beginning on every resumption, but activities whose results are already recorded get skipped. This lets you write workflows that look imperative while getting durability guarantees.

The trade-offs are operational complexity (you need to run the Temporal server, which needs its own database and potentially Elasticsearch), a steeper learning curve (the distinction between workflows and activities, determinism requirements, and replay semantics take time to internalize), and the fact that workflow state lives outside your Rails database. For teams already running Kubernetes with dedicated SREs, these may be acceptable costs. For a Rails team that wants workflows without introducing new infrastructure, they may not be. There is also a layer of “we pretend to need extreme performance” involving waiting on an Activity using fibers, and downright Ruby-hostile components like gRPC to take into account.

And the most important of all: I find Temporal incredibly over-engineered. If you already have most of Rails at your disposal, using Temporal is like having to install a Panamax supertanker to refuel your Honda Civic.

Geneva_drive is not trying to compete with Temporal on features. It is trying to provide “good enough” durable workflows for Rails applications, without having to deal with all of that stuff.

Do take it for a spin!

geneva_drive is already in production at Cora and at a couple of other fairly high-intensity applications, with great results. It is the distillation of several years of experience working in fintech and a couple of decades of Rails, and I am convinced it is better than “passable” - it has great future.

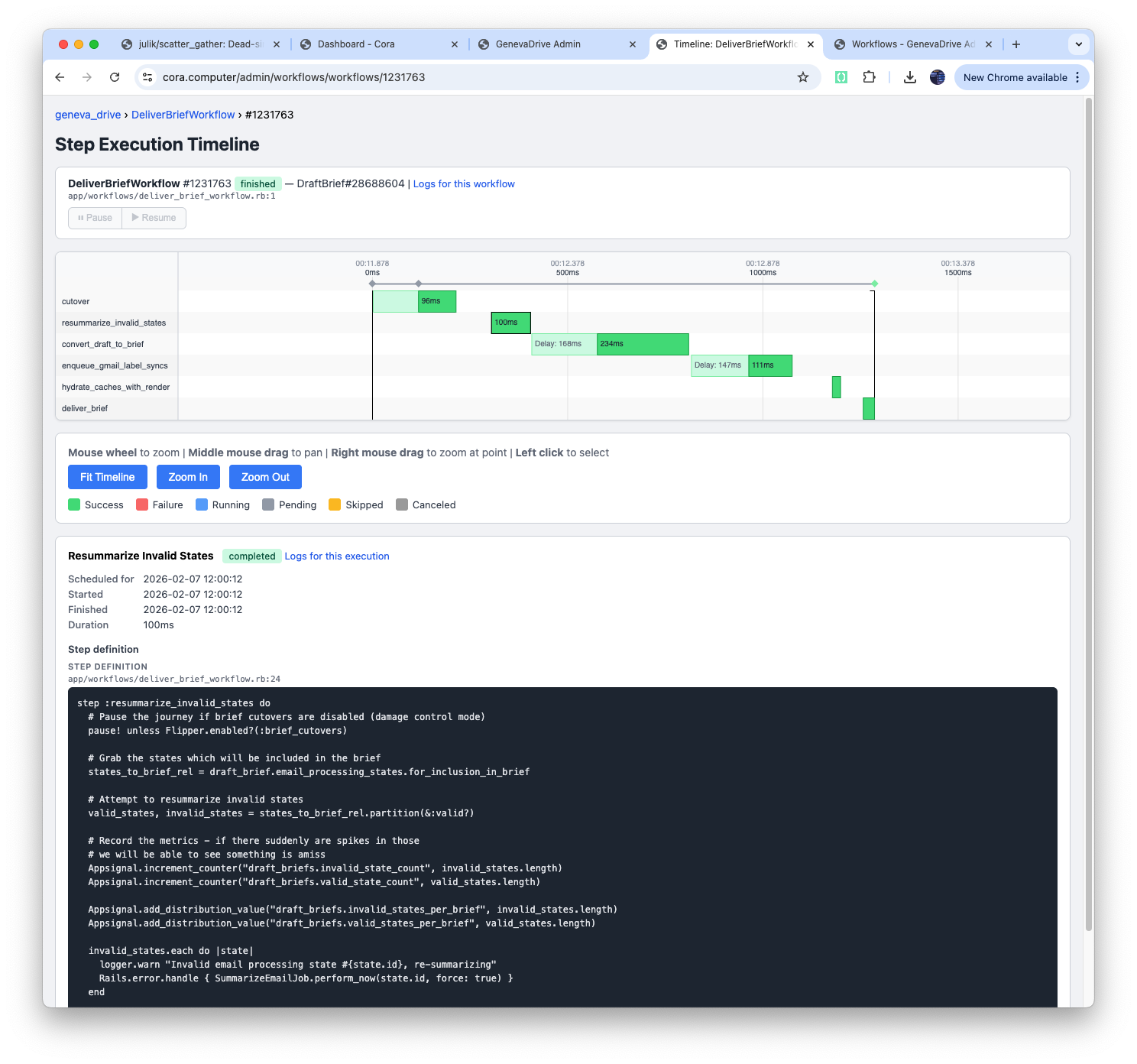

The source code is at github.com/julik/geneva_drive, licensed under LGPLv3. A commercial version is already available, which includes a fabulous admin UI - I will be posting more about its workings soon - and the removal of the restrictions of LGPL should your company require it. As a teaser, here is how a workflow looks when displayed by the workflow timeline visualiser that you get in the admin:

If you are just starting on your product, we may be able to work out a good pricing for you - under the condition that you provide feedback about what is working and what is missing for you to be successful with geneva_drive. I would love you to build something awesome with it.