On the way to step functions: it is actually a DAG

This is the next article in the series On the Way to Step Functions — you can find the first article in the series here. Previously, I have outlined the ambient desire in the field (marshalable stacks) and described why that is largely unachievable. But if imperative invocations can’t bid us consolation, what could?

DAGs, in fact.

If you are impatient (and a Rails user) - just head to the geneva_drive repo for the grand reveal.

This post is part of a series:

- On the way to step functions: Part 1

- On the way to step functions: Part 2

- On the way to step functions: Part 3

- On the way to step functions: Part 4

🧭 I am currently available for contract work. Hire me to help make your Rails app better!

DAGs, DAGs everywhere

I love DAGs (directed acyclic graphs). DAGs are everywhere.

Having worked in visual effects for a while, I know first hand that most of the professional apps implement some version of a DAG. DaVinci Resolve does. Nuke does. Houdini does. Maya, Fusion, Blender, Flame… the list goes on and on.

The interesting bit is that those systems, while seemingly far estranged from payment processing and other “cloud” workloads, are - in essence - deferred computation engines. Since performing the actual processing (rendering, generation etc.) in those systems can be extremely computationally intensive, placing those computations behind nodes makes for a great way to stabilise and cache the results of those computations. Moreover - to a certain degree using DAGs allows the results to be retained, provided that the dependencies of the nodes do not influence the results of the computation. For example, a node that generates a piece of platonic geometry can be a “leaf” node and not have any dependencies at all - it only has parameters. Therefore, it can not only be reconnected into other dependent nodes - it can also be duplicated, and reuse the stored result of the computation in all of the instances thus created.

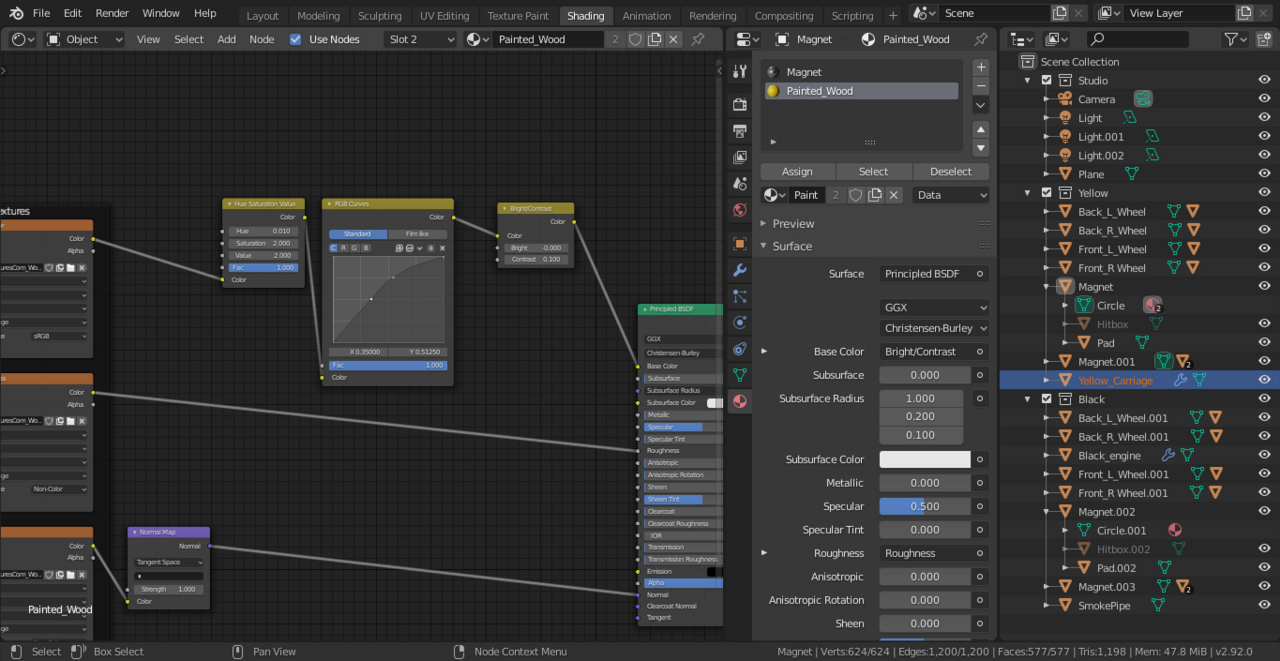

This is what node graphs tend to look like in practice (example: Blender shader nodes):

Nuke and Autodesk Flame have similar node graph setups, adapted to their respective domains.

Instead of imperatively specifying the execution flow a DAG specifies a tree of dependencies. When Stephen Margheim was picking up work again on acidic_job I’ve asked him about DAGs, and that was for a good reason. If we ignore structured rollbacks (sagas), any such step computation is, actually, a DAG. The “workflow” - the brittle, squishy part responsible for orchestration - lives in the DAG, the nodes and the connections between them. The imperative code that “does stuff” lives in the nodes themselves, oblivious to the fact that it is controlled “from the outside”. And the DAG is, by definition, declarative.

But VFX software is by far not the only rendition of DAGs. Just look at Terraform:

module "app" {

source = "../../modules/app_engine_flex"

project_id = module.thefirm_project.project_id

resource_prefix = module.thefirm_project.project_name

services = {

default = {

allow_external_traffic = true

}

}

artifacts_project_id = var.artifacts_registry_project_id

subnet_name = var.subnet.name

}

The app here is a Node in a DAG. It has thefirm_project as well as var as its dependencies - before they get resolved, the app node cannot be resolved. When doing a “plan” (or an “apply”), Terraform will build out the dependency graph of the resources that need to be modified or created to satisfy dependencies of their downstream resources, perform a topological sort, and start with resolving var and thefirm_project before trying to resolve app. There are other peculiar tidbits that allow Terraform to function as a DAG. For example:

resource "random_id" "db_suffix" {

byte_length = 2

}

Seemingly, this would be a value which would completely throw off repeated computation for Terraform. Every time we evaluate the DAG, there would be a new random ID generated by this resource, right?

Right. However, Terraform has this thing called state. The Terraform state is effectively a materialized version of checkpoints, for every node in the graph. Once the db_suffix resource gets resolved by Terraform, its computation result will be saved into the Terraform state, and frozen until the parameters of the resource change. byte_length changing would lead to Terraform regenerating the random value. So even though the node is supposed to generate a random value, that value then gets cached and reused - making it an idempotent computation.

If there were a resource called payment_request which would need an idempotency key, it would be to the author of the Terraform provider to ensure the idempotency key either does not bleed into the orchestration / node checkpoint at all (and is thus always random), or that it gets persisted into the checkpoint and remains stable.

In Nuke or Resolve a similar trick is employed. If you have a node which generates random noise or grain, it would be parametrised by a known seed value. That seed value would be one of the node’s parameters, and would be persisted with the DAG. Rerunning the node’s code should produce exactly the same noise output. The node is thus coded to be idempotent. In this instance, idempotency is also an inherent requirement - but this requirement exists on the level of nodes, not on the level of the orchestrating workflow.

Turning our invocation into a DAG

Let’s get back to our example:

authorisation_result = run_remotely_and_asynchronously(:authorise_payment)

funds_check_result = run_remotely_and_asynchronously(:check_funds)

sleep until authorisation_result.received? && funds_check_result.received?

transfer_result = run_remotely_and_asynchronously(:transfer_funds)

run_remotely_and_asynchronously(:send_email) if transfer_result.ok?

sleep 10.days

mark_payment_as_final

What we have before us is imperative code - or as close as we can get to imperative code. But we can also represent this workflow as a graph of nodes. If we assume that fetching the result of a run_remotely_and_asynchronously call equates to needing that result as a dependency for the actions taking place down the program, a DAG representation (assuming a DSL for defining DAGs) could look like this:

authorisation = dag.create_node(:authorise_payment)

funds_check = dag.create_node(:check_funds)

join = dag.create_node(:wait_for_all_inputs)

join.connect_inputs(authorisation, funds_check)

transfer_result = dag.create_node(:transfer_funds)

transfer_result.connect_inputs(join)

email = dag.create_node(:send_email)

# We need some form of branching -

# this could be one of the possible ways

email.connect_inputs(transfer_result.ok_output) # There would also be Node#error_output

wait = dag.create_sleep(10.days)

wait.connect_inputs(email)

finalize = dag.create_node { mark_payment_as_final }

finalize.connect_inputs(wait)

Or, visualised:

graph TD

A[authorise_payment] --> J[wait_for_all_inputs]

F[check_funds] --> J

J --> T[transfer_funds]

T -->|ok_output| E[send_email]

E --> W[sleep 10.days]

W --> FIN[mark_payment_as_final]

We could then call our finalize.resolve! to run through the nodes in order. Since this is a DAG, you would run some kind of topological sort first, to resolve the dependencies of all the nodes in your workflow. A topo sort would reveal that you need to resolve authorisation and funds_check first, and since they do not depend on anything common, they can be run in parallel.

The obvious item we would need to solve in this situation would be the checkpointing. Node-based system such as the one in Nuke implement it in a fairly interesting way. When the nodes get evaluated, there is a CacheHash object passed through them. Every node is able to do roughly this:

cache_hash_for_this_branch << self.stable_cache_key_for_source_file

cache_hash_for_this_branch << self.random_seed_used_for_queries

The cache key for a Node would be an amalgamation of the node’s CacheHash and the CacheHash values of all the node’s inputs - you could see it as a Merkle tree of sorts.

Any change in the input configuration (or in the upstream node parameters) would invalidate that cache. It is a bit baroque but quite effective, unless the graph gets reconfigured - remember what I’ve written about the code of the invocation being stable? With a DAG there can be a formal definition to this stability within the scope of a section of the DAG’s edges - a set of nodes with parameters, connected to one another, remain a stable invocation as long as the parameters of the nodes and the inputs do not change.

Steps are just a subset of a DAG

If we treat our workflow as a sequence of steps, like this one (we’ll use a trimmed example of our previous workflow):

authorisation_result = run_remotely_and_asynchronously(:authorise_payment)

funds_check_result = run_remotely_and_asynchronously(:check_funds)

sleep until authorisation_result.received? && funds_check_result.received?

transfer_result = run_remotely_and_asynchronously(:transfer_funds)

run_remotely_and_asynchronously(:send_email) if transfer_result.ok?

sleep 10.days

mark_payment_as_final

we can also turn it into a DAG with a slightly different configuration (using our previous translation of this code into DAG nodes and connections):

authorisation = dag.create_node(:authorise_payment)

funds_check = dag.create_node(:check_funds)

join = dag.create_node(:wait_for_all_inputs)

join.connect_inputs(authorisation, funds_check)

transfer_result = dag.create_node(:transfer_funds)

transfer_result.connect_inputs(join)

email = dag.create_node(:send_email)

# We need some form of branching -

# this could be one of the possible ways

email.connect_inputs(transfer_result.ok_output) # There would also be Node#error_output

wait = dag.create_sleep(10.days)

wait.connect_inputs(email)

finalize = dag.create_node { mark_payment_as_final }

finalize.connect_inputs(wait)

What do we lose in this instance? Simple: the ability to run 2 nodes (check_funds and authorize_payment) in parallel. Sometimes it can be a blocker, sometimes not. But what we gained is that we could turn our DAG into a stack.

This has a number of massive, massive benefits:

- We do not need to worry about “some failed” situations

- We do not need to do the topo sort - the steps always resolve top-down

- We do not have any fork-and-join problems

And since our steps are a subset of a DAG: we can, later on, redesign our system in such a way that it will become able to do fork-and-join and be a DAG.

So: while your step workflow is going to be a DAG under the hood, it is feasible to design it so that you don’t need a DAG immediately.

To recap

Most - if not all - “durable execution” systems will usually build on top of “workflows” where every “workflow” is actually a DAG. The amount of pretense that it is not so will depend on the sophistication of the developers of the workflow system in question.

Stay tuned for Part 3, where we explore how these “two worlds” - the DAG and its nodes - interact!