On the way to step functions: the two worlds

This is the next article in the series On the Way to Step Functions - you will find the other articles linked below:

- On the way to step functions: Part 1

- On the way to step functions: Part 2

- On the way to step functions: Part 3

- On the way to step functions: Part 4

We have highlighted that DAGs are actually the underpinning of any workflow/durable computation engine (barring serializable continuations). I would like to highlight another aspect of that reality: that there are two worlds.

TL;DR - if you are a Rails user and that topic interests you, skip away to geneva_drive which is pretty much how I feel we “should do it” in Rails-land.

🧭 I am currently available for contract work. Hire me to help make your Rails app better!

The magic wall

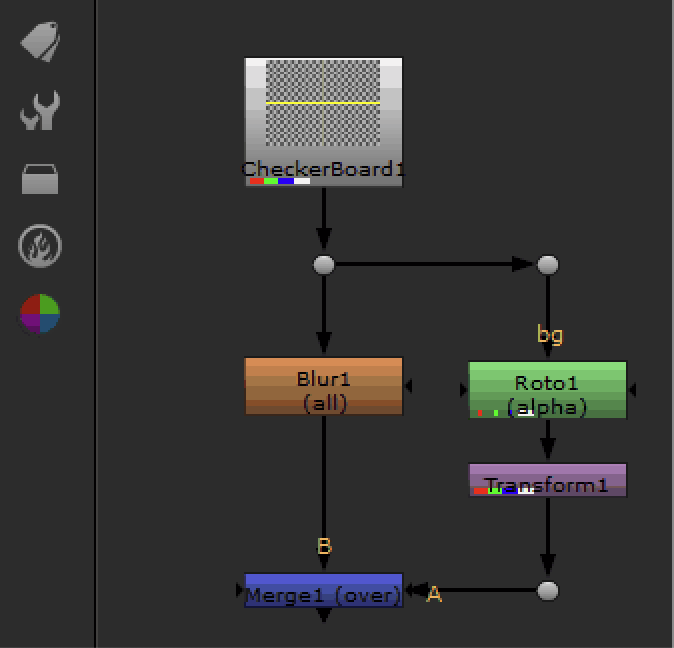

The DAGs we use in professional graphics or audio apps have a very interesting property: the workspace consists of two worlds, and these two worlds are segregated by very strict - and limited - interfaces. For example, here is the UI of Nuke again:

The nodes that we see in the graph form part of what is called a Nuke script. A working Nuke file is actually a script in a near-forgotten scripting language called Tcl. Working files for both Shake and Nuke are, historically, scripts - because both applications were designed to work without a GUI at all. They were built as headless render engines for files produced by other applications (or written from scratch).

A Nuke script has the following shape:

set cut_paste_input [stack 0]

version 6.3 v4

CheckerBoard2 {

inputs 0

name CheckerBoard1

}

Blur {

size

name Blur1

selected true

xpos -212

ypos -24

}

We have a CheckerBoard2 node with no inputs. Then the output of the checkerboard is fed into a Blur (it being right below the checkerboard node means that it accepts the output from the checkerboard - the order of nodes is used for implicit stacking). The size parameter of the Blur is also animated, which is done using the `` expression braces.

But there is something else too! The CheckerBoard2 actually instantiates an object in native code, which is compiled from a source file called CheckerBoard2.cpp. The code that defines the workflow is one entity, while the code that runs inside the nodes is a completely different entity.

And they never intertwine except via the exposed properties from the DAG. The Nuke engine has various handles exposed from CheckerBoard2 for caching, for rendering a pixel or rendering a scanline from it, for getting the image bounding box of the node and for setting its initial parameters. But note that the script does not contain the definition of the CheckerBoard2 module itself!

Moreover: there is absolutely no way for the script to call things on the module or control it imperatively. The workflow engine (the Nuke engine) establishes bindings between the values and expressions in the script, and passes the values in one direction only into every particular node.

When doing the render, Nuke passes the buffer into which the node shall output its rendered pixels as an argument (it is a C++ reference variable for every image row, but that’s an implementation detail) - it collects the result. The result may then be cached somewhere, or the engine may elect to use that cached result and not call the module at all. Or the node may be disconnected from any further outputs - and will then be skipped from initialization.

But the most important trait of this system is that it is effectively 2 separate environments: the declarative code of the workflow and the imperative code of every node, which runs parameterized with the node’s inputs and properties.

The node’s code must also be idempotent.

And these worlds never meet.

Congratulations, now your functions have 3 colors

I do not find it strange that most workflow systems attempt to fuse these two worlds at any cost. For example, ActiveJob Continuation does its best to stuff all of the step definitions inside of the perform method of the job class. Temporal is trying desperately to make the entire workflow controllable from a single imperative workflow, under the pretense that it can somehow work - and it does, like any highly leaky abstraction.

You just have to use gRPC, a special flavour of sleep, a special flavour of… anything, really - but I digress.

Similar for the Vercel workflows and use workflow. What happens if you do not have a use workflow (and a JS transpiler - you seem to need a JS transpiler for every teensy little thing these days)? Well, every async invocation may crash and you will have to restart from scratch. There are implicit checkpoints, but where will they be? What are the guarantees that you won’t rerun what has already run, and is there a guarantee that what gets await-ed on will be idempotent and produce the same output on every invocation?

Nothing. No - really - while it is very tempting to pretend that you can dispense with that separation without having an entire virtual machine for it - it will not become more robust, or easy to understand, or particularly more “user friendly” because that blending gives your code blocks color, and not in a good way. Remember the epic What Color Is Your Function essay? Merely using async has your program run with 2 colors:

// paymentResult and everything around is mostly "red", what happens inside

// performPayment is "blue".

const paymentResult = await performPayment(paymentRequest);

But blending your DAG and your imperative node code now has your code in 3 colors, with wildly different traits. The two we already know:

"use workflow" // This turns the entire "outer" code section "green"

const token = generateToken(); // This chunk is "red" - maybe

const paymentResult = await performPayment(paymentRequest, token); // This is "blue"

…are likely going to be transformed by the “workflow compiler” to have checkpoints where it can see you are calling an async function:

"use workflow" // This turns the entire "outer" code section "green"

const token = generateToken(); // This chunk is "red" - maybe

__magicalWorkflowRuntime.stackPush("token", token)

__magicalWorkflowRuntime.checkpoint(__LINENO__)

const fut = __magicalWorkflowRuntime.futurePromise(__LINENO__, () => {

return performPayment(paymentRequest, token);

});

__magicalWorkflowRuntime.stackPush("paymentResult", fut);

__magicalWorkflowRuntime.checkpoint(__LINENO__)

You don’t know how the “green” chunk of code will suspend or resume. You don’t know what the idempotency guarantees are in it. If you call the following code in your “green” section, what will happen?

"use workflow" // This turns the entire "outer" code section "green" (replayed + suspendable)

const started = performance.now(); // "red": time is non-deterministic across suspend/resume/replay

const token = generateToken(); // "red": randomness / one-time values (non-deterministic)

const paymentResult = await performPayment(paymentRequest, token); // "red": external I/O (retried / resumed elsewhere)

const balanceAfter = extractBalance(paymentResult); // "blue": pure/deterministic sync computation

const timeTaken = performance.now() - started; // "red": meaningless if the workflow suspends between the two calls

We want to measure how long the payment flow took end-to-end, but we can’t! The fact that our “body of code” blends the three different execution flows (sync functions, async functions and suspendable workflow code) means that our second invocation of performance.now() is going to run on a completely different machine than our first invocation, and it will almost certainly not provide us with a value that makes sense (unless the runtime overrides performance, which - in the usual Vercel fashion - will likely be done, with disastrous consequences).

But the fact that these two are one and the same body of code lull you into a fake sense of familiarity. It is a lie, and a damn sneaky one.

The two worlds

The definition of the DAG and the code that runs inside its nodes are two completely separate entities. In Terraform, the DAG is defined in HCL and converted into the “state” - a reconstruction of the world with in-memory handles to the nodes. The “providers” - imperative code written in Go - actually execute those nodes. These two worlds only ever combine during the execution of the Terraform tasks.

In Nuke, the “script” (working document) is a description of a DAG which gets loaded into memory and the nodes are, again reconstructed with references to each other. The shared libraries - one library per node implementation - is the imperative code written in C++ which actually executes those nodes. These two worlds only ever combine during the rendering (or previewing) your Nuke scene.

Let’s take a look at “use workflow” from Vercel as the latest example of “just keep pretending it’s all one big function, folks!” Sure, it looks lovely: you get to write a single chunk of code, with all the comforting imperative trappings. Sleep here, branch there, loop around—ah, the sweet illusion of continuity! But here’s the punchline: it’s always been a fantasy. All of history’s best practitioners—visual effects applications, Terraform, you name it—acquired their rigor precisely by separating what needs to be done (the declarative world—the DAG) from how it’s actually done (the imperative “do the thing” world). And for good reason: execution is not the same as orchestration!

Insisting on bodying everything up into one pseudo-imperative blob just brings you tricksy bugs and mental contortionism. You start believing that your stops and waits and forks will always “just work” because… JavaScript closure magic will save the day? Please. Ask anyone who tried marshalling a deeply nested workflow stack into the ether and back if they slept well that week.

Embracing DAGs for workflows is the real creative victory here. The moment you admit that the orchestration “map” is a DAG, you unshackle yourself: each step can be resolved, cached, retried, and orchestrated independently. You gain parallelism for free; you can swap nodes and reroute dependencies without rewriting every last “await” or “yield.” It’s not a cop-out or a constraint—it’s liberating. The sooner we stop pretending that everything is “just a function” and instead acknowledge the power of the DAG, the more future-proof, testable, and pleasant our workflow systems become. Vercel, call me when you’re ready to come to Nodes School.

A word of warning about YAML

It will, of course, be very tempting to say “well, if the DAG should be declarative - why not make it YAML?”

As a matter of fact, HashiCorp have stopped just short of that with Terraform - except they have invented their own language instead. Most systems that come from the computing platforms world insist on using YAML for declarative portions of the code.

Sadly, this is not because “YAML is declarative”. It is because YAML is a least common denominator - the terrible thing everybody could agree on. See, Python folks hate Ruby folks. Ruby folks don’t hate anyone but they don’t like writing Python. Go folks think that both Ruby and Python folks are losers. Rust folks think that all the other folks are quite cute, but whatever they use is a toy anyway. JS folks think that everyone is stupid and that the majority rule by steamrolling will, in the end, make everything JS.

So when the time came to have some kind of declarative language for things like configurations and DAGs, the compromise became YAML. While HCL is a nice departure from YAML it is still very un-ergonomic for someone coming from Ruby or Python - and needlessly so, because while any language can produce a non-deterministic workflow definition, having a language for this you know intimately well will be a better option.

So: if you ever go into durable workflows, make it possible to define the DAG in whatever language that is native and pleasant for the ecosystem(s) you want users in.

To recap

The definition of the DAG and the code that runs inside its nodes are two completely separate entities. In Terraform, the DAG is defined in HCL and converted into the “state” - a reconstruction of the world with in-memory handles to the nodes. The “providers” - imperative code written in Go - actually execute those nodes. These two worlds only ever combine during the execution of the Terraform tasks.

In Nuke, the “script” (working document) is a description of a DAG which gets loaded into memory and the nodes are, again reconstructed with references to each other. The shared libraries - one library per node implementation - is the imperative code written in C++ which actually executes those nodes. These two worlds only ever combine during the rendering (or previewing) your Nuke scene.

Most - if not all - “durable execution” systems will contain imperative parts (the steps/nodes) and declarative parts (the DAG describing your workflow). These two parts have wildly different semantics, guarantees and requirements. Systems that pretend they are one and the same - will create much more pain for their users than those which do not.

Stay tuned for Part 4, where we will take a look at how those workflows could work quite nicely in Ruby and why the existing solutions (active-job-iteration, ActiveJob::Continuation, temporal-ruby etc.) are not quite up to snuff.